How Adjusting the ‘Immigration Registry’ Could Help Intercountry Adoptees

Two years ago I drafted a legal memorandum about updating the U.S. ‘immigration registry’ and how that tweak could secure a path to citizenship for intercountry adoptees in the United States. It was part of an overall effort by a number of lawyers to explore legal options in the face of the stalled efforts to fix a legal loophole that has denied U.S. citizenship to thousands of intercountry adoptees. The original memorandum is here, and I have included portions of what I wrote below. I also outline what updating the registry date would mean to millions of people who currently have no meaningful path to citizenship, including intercountry adopted people living in the United States.

The so-called “registry” provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act provides a way for persons who have resided continuously in the United States but do not have current legal status to apply for and receive, at the discretion of the attorney general, admission as a legal permanent resident. It currently applies only to people who entered the United States prior to January 1, 1972. It is often known informally as “the registry” or by Section 249.

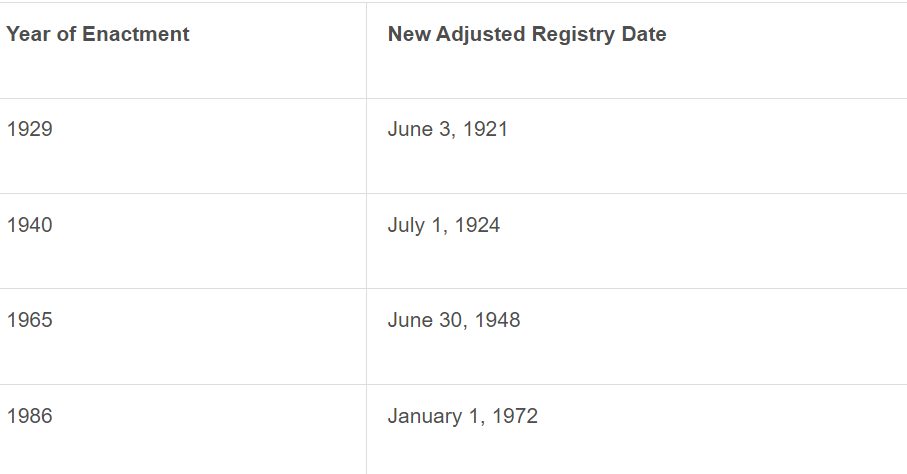

The registry has been in U.S. immigration law for nearly 100 years. Congress first included a registry provision in the law in 1929, and it applied to those who had entered the United States prior to June 3, 1921. Over the years, Congress adjusted the date periodically, as follows:

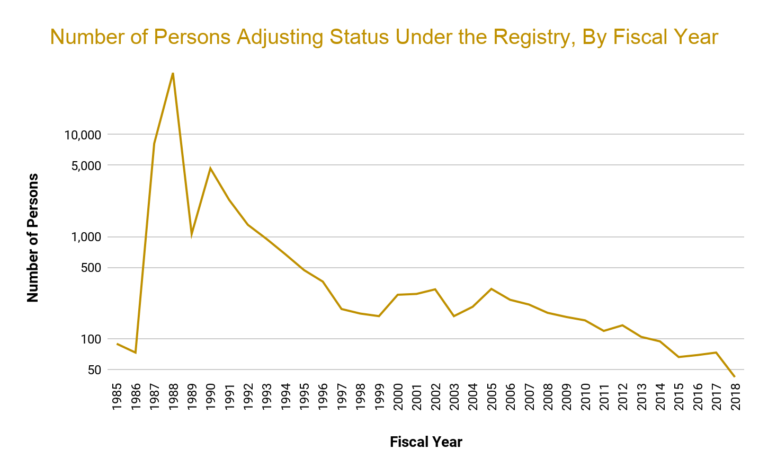

The registry date—which had previously been adjusted on roughly generational time frames of 20-25 years— has not been adjusted for decades, resulting in a nearly 50-year gap between the registry date and the current year. The Clinton Administration sought to adjust the date to January 1, 1986, but those efforts did not lead to a change. Congressional representatives have continued to introduce bills for many years to adjust the date, but those bills have never passed. Because the date has not be adjusted, fewer than 100 people have used the registry to become legal permanent residents during the 2018 and 2019 fiscal years.

Who Does the Registry Help?

The registry is viewed as a way to secure a path to citizenship for people who have lived continuously and without issue in the United States for a set period of time but have no current way to become U.S. citizens.

What are the Current Requirements of the Registry?

The registry provision currently applies only to those people who entered the United States prior to January 1, 1972. In addition, the law requires that the person

- has continuously resided in the United States since entry;

- has good moral character;

- is not ineligible for citizenship; and

- is not inadmissible as a participant in Nazi persecutions or genocide or on grounds related to “criminals, procurers and other immoral persons, subversives, violators of the narcotics laws or smugglers of aliens”

- must not be deportable for engaging in espionage, for threatening national security, or for engaging in terrorist-related activities.

The registry does not apply to people who are already legal permanent residents in the United States. Rather, the registry provides a way for people who have resided in the country continuously to become legal permanent residents and, if successful, later apply for citizenship through naturalization.

What is Being Discussed or Proposed Today?

When the Senate parliamentarian recently rejected a Democratic plan to use procedural rules to pass comprehensive immigration reform, efforts moved to pursuing a “Plan B.” That plan has allegedly included an effort to adjust the registry date, which could affect up to 11 million undocumented immigrants, depending on what date is agreed upon.

How Many People Would Benefit from an Adjusted Date in the Registry?

In 2001, it was estimated that approximately 500,000 people would have been eligible to adjust status under the registry provision if the date was simply adjusted by fourteen years, to January 1, 1986. Far more people would now qualify to become legal permanent residents through the registry if the date was adjusted to a more recent timeframe. For instance, an estimated 6.8 million people would qualify under the registry if Congress adjusted the entry date to 2010, and an estimated 11 million people would benefit if it was adjusted to at least 2015.

How Could a Change in the Registry Help Intercountry Adoptees without Citizenship?

An adjustment to the registry date would help two primary groups of intercountry adoptees without U.S. citizenship:

- adopted people who entered the country on a non-immigrant visa (e.g., a tourist or “visitor” visa or a visa based on humanitarian grounds) and

- adopted people who may lack a record of entry into the country;

An adjusted date to 2010 would cover the vast majority if not all of these two groups of adoptees. I currently have four clients who would directly benefit from a change in the registry and would, as a result, have a clear path to U.S. citizenship. I also know of many others who would also benefit from the change.

Will It Help All Intercountry Adoptees without US Citizenship?

No. It will not help the vast majority of intercountry adoptees who currently lack U.S. citizenship. Intercountry adoptees who are already legal permanent residents but who have not naturalized—or have barriers to naturalization—will not benefit from an adjustment in the registry. In addition, intercountry adoptees who have been deported would also not benefit from a new registry date, as they do not currently reside in the United States. Enacting the current Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2021, however, would provide automatic citizenship for many intercountry adoptees and it would also establish a path toward citizenship for adoptees who have previously been deported.

Conversely, an adjusted registry date would likely benefit a class of adoptees who may ultimately receive no immediate relief from passage of the Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2021.

Does it Provide Citizenship if you Qualify?

No. Unlike the Adoptee Citizenship Act, qualifying for the registry does not provide U.S. citizenship. Rather, it allows a person to become a legal permanent resident. The person can later apply for naturalization three to five years after becoming a legal permanent resident. Automatic citizenship, however, may be possible if an intercountry adoptee becomes a legal permanent resident first, before the enactment and effective date of the Adoptee Citizenship Act (presuming it is enacted).